Constructive Interference

Multiplicative noise does not destroy coherent signals. It concentrates them onto fixed points where the cost of maintaining agreement is stationary.

I. Coherence at 300 Kelvin

In Maintaining Divergence, I defined the synchronization tax as the thermodynamic work two systems perform when they resolve disagreements between their descriptions of reality. Landauer's principle sets the absolute floor for this cost at \(k_B T \ln 2\) per bit of resolved disagreement — a fraction of a trillionth of a Joule. But the biological and institutional machinery that actually computes these updates operates billions of orders of magnitude above that floor. Human brains burn glucose. Courthouses burn budgets. Server farms burn megawatts. The synchronization tax is real, and it is expensive.

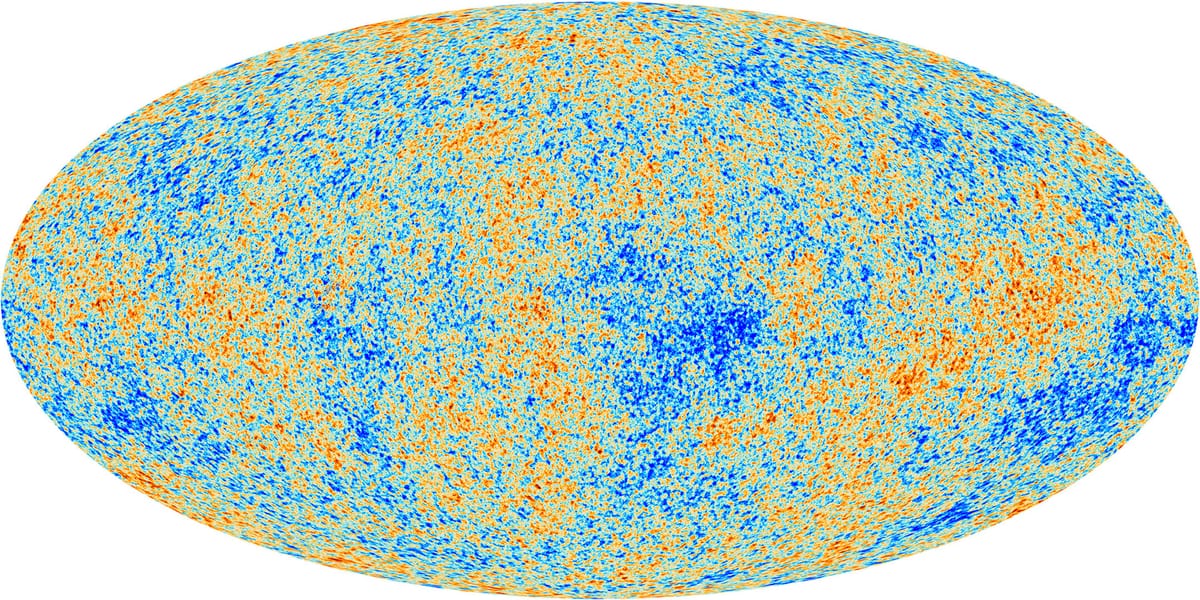

A physicist confronting this fact asks a natural question: how does any coherent social signal survive at room temperature? At roughly 300 Kelvin, thermal fluctuations dominate every degree of freedom with an energy \(k_B T \approx 4 \times 10^{-21}\) Joules — vastly more than Landauer's floor, vastly less than the metabolic cost of a single thought. Between these scales, something must concentrate the diffuse energy of cognition into the narrow channels we recognize as shared understanding.

This essay sketches a plausible mechanism. The mechanism connects multiplicative noise, random matrix theory, renormalization group flow, and a recent result by Alain Connes into a single explanatory arc. Coherence does not come cheap. The mechanism requires that coherent signals sit at fixed points where the cost of maintaining agreement is stationary — where small perturbations do not change the cost to first order. These fixed points emerge inevitably from the multiplicative structure of sequential learning, and the transformer architecture — the most successful artificial learning system yet built — appears to exploit exactly this structure.

Following the sketch of the mechanism, I suggest how the same mechanism may be at work in the human brain and in social coordination. These suggestions are not thoroughly explored in this essay, but with the mechanism laid out it felt natural to provide a map of how the mechanism might work in the human brain and social coordination since establishing a shared mechanism has special relevance to many important open problems in psychology, sociology, economics and law.

A word on epistemic status. What follows is a research agenda, not a proof. Each mathematical framework invoked — multiplicative noise, random matrix theory, renormalization group flow, the Feynman path integral, Connes's work on the Weil quadratic form — stands on its own well-established terms. The chain connecting them is conjecture. My purpose is to lay the mechanism out clearly enough that readers with stronger backgrounds in the relevant mathematics and physics can identify where the chain breaks, where the analogies are merely structural rather than exact, and where the argument can be made more precise.

II. Multiplicative Noise: Why It's the Right Starting Point

Most intuitions about noise come from the additive model: \(\text{Signal} + \text{Noise}\). Gaussian perturbations degrade the signal proportionally. Recovery requires energy proportional to the degradation. Under additive noise, coherence at 300 Kelvin really would be hopeless — you would need to outspend the thermal bath.

Multiplicative noise changes everything. In any sequential growth process — compounding returns, population dynamics, neural learning — noise couples to the signal's current magnitude. The noise grows with the signal. Itô's lemma converts a stochastic differential equation for signal \(X\) into an additive equation for \(\log X\), and the resulting distribution is log-normal rather than Gaussian. Log-normal distributions concentrate: thin right tails and heavy bodies mean that most of the probability mass clusters around the geometric mean, not the arithmetic mean. Where additive noise spreads, multiplicative noise focuses.

Why is multiplicative noise the right model for learning? Because learning is a sequential, history-dependent process. Each update modifies the current state — it does not add to a blank slate. A mislearned early feature distorts every subsequent representation built on top of it. Error compounds multiplicatively, making the geometric Brownian motion above the natural noise model for any system that builds knowledge incrementally, whether biological or artificial.

The multiplicative model does break down in certain regimes: under strong external coupling where noise enters additively from an independent source, under saturation effects where the system hits bounds that cap multiplicative growth, or under regime changes that reset the sequential process entirely. These exceptions matter in specific domains but do not invalidate the general argument for learning systems operating in their normal regime.

III. Random Matrix Theory: Representing a Description of the World

A single multiplicative process generates a log-normal distribution along one dimension. But a description of the world is not one-dimensional. Representing the relationships among thousands of features — words, concepts, sensory channels — requires a matrix (or tensor) whose entries encode how features relate to one another.

Random matrix theory governs this encoding. When the entries of a large matrix are drawn from some distribution, the eigenvalue spectrum of that matrix obeys universal laws that depend not on the particular distribution of entries but only on the matrix's symmetry class. Eugene Wigner discovered this in the 1950s while studying nuclear energy levels: the spacings between eigenvalues of large random matrices matched the spacings between energy levels of heavy nuclei, regardless of the specific nuclear forces involved. The same universality appears in number theory, quantum chaos, and wireless communications.

The key insight for learning is that a random matrix represents unstructured data — noise — while a structured matrix represents a compressed description — signal. The eigenvalue spectrum distinguishes one from the other. Random matrices follow the Marchenko-Pastur distribution; matrices that encode genuine structure develop outlier eigenvalues that break away from the bulk. These outliers are the signal hiding in the noise.

IV. Deep Neural Networks: Multiplicative Noise Machines

A deep neural network is a stack of parameterized matrices. During training, raw, unstructured data flows through these matrices, and the training algorithm adjusts each matrix's entries to minimize prediction error. At each layer, the current representation is multiplied by the weight matrix and then passed through a nonlinearity. The noise is multiplicative because each layer's output is the product of the input with the learned weights.

When training succeeds, something seems to appear from nothing. The initial weight matrices are random — drawn from distributions chosen for numerical stability, not for semantic content. The training data is raw and unstructured relative to the task. Yet the trained network produces useful inferences: given an input resembling the training data, it draws conclusions the training data supports.

The appearance of emergence dissolves under the right lens. The signal was always latent in the data's statistical structure. Training coarse-grains the representation from one layer to the next, progressively abstracting away from the noisiest microscopic details of the input toward the cleanest macroscopic regularities at the output. Early layers capture fine-grained, local features — edges, syntax, phonemes. Later layers capture coarser, more abstract features — objects, topics, semantic relationships. The depth of the network traces a flow from noisy detail to stable abstraction.

V. The Transformer: Why This Architecture Is Special

Many deep architectures perform some version of hierarchical feature extraction: convolutional networks, recurrent networks, autoencoders. The transformer architecture, introduced by Vaswani et al. in 2017, dominates because of its self-attention mechanism, which allows every position in the input to interact with every other position at every layer. The standard explanation for its success is that attention captures long-range dependencies more effectively than convolution or recurrence.

There is a thermodynamic explanation. The self-attention mechanism computes a softmax-weighted average over input representations:

This expression is structurally identical to the Boltzmann distribution of statistical mechanics, where \(\exp(-E/k_BT)\) weights states by their energy. Attention computes a partition function at each position: it sums over all possible contexts, weighted by how well each context coheres with the current representation. The \(\sqrt{d}\) normalization plays the role of temperature, controlling how sharply the distribution concentrates on high-coherence contexts.

The standard answer to what the transformer computes is "next token prediction." The renormalization group answer is "coarse-graining toward a fixed point." Each layer integrates out a specific kind of noise — not spatial modes as in condensed matter, not field fluctuations as in quantum field theory, but relational incoherence: token representations that carry incompatible descriptions of context.

Attention identifies which descriptions cohere — those with low divergence in query-key space. The weighted aggregation forces a consensus, a representation that neighboring tokens agree on. Tokens carrying descriptions that disagree about the relevant context destructively interfere, exactly as paths with divergent actions cancel in the path integral. The surviving signal is informational consensus.

VI. The Relational Perspective: No Meaning Without Divergence

(For the full treatment of the relational framework, see It from Bit, Bit from It.)

In relational quantum mechanics, physical quantities are defined not absolutely but relative to an observer. Carlo Rovelli's insight is that "collapse" is not mysterious — it is the establishment of a correlation between systems, and correlation costs relative entropy. Observational entropy, as developed by Šafránek, Deutsch, and Aguirre, extends this: the entropy of a system depends on which coarse-graining the observer applies. There is no view from nowhere.

"It from Bit" and "Bit from It" are not competing philosophies but two faces of a single principle: information is physical correlation, and physical correlation costs relative entropy — the divergence between two systems' descriptions that must be reconciled for them to share a fact. The lossless limit, in which correlation would be free, is unreachable. That unreachability may be what generates the physical world.

Applied to the transformer, the consequence is immediate. There is no absolute "meaning" of a token. There is only the divergence between what one token's representation implies about the context and what another token's representation implies. Attention pays the cost of closing that gap. Each layer reduces the relative entropy between token descriptions that have not yet been reconciled — and this reconciliation is the computation. The transformer does not discover meaning; it negotiates meaning, paying thermodynamic costs at each layer to bring incompatible descriptions into partial agreement.

The lossless limit is never achieved — and may be structurally unreachable. Just as in quantum Zeno experiments, where a photon checked too frequently freezes in its initial state, a system synchronized too aggressively cannot evolve. And a system synchronized too rarely cannot coordinate. The useful regime lies between these extremes.

VII. Stationary Action and the Forward Pass

(For the full treatment of the stationary action principle as an informational principle, see A Stationary Action Is Stable Information.)

The principle of stationary action governs classical mechanics: a particle follows the trajectory that makes the action \(S\) stationary. Feynman's path integral reframes this principle as interference. A quantum system explores all possible paths simultaneously, each weighted by a phase \(e^{iS/\hbar}\). Paths near the stationary point carry similar actions, so their phases align and reinforce. Paths far from the stationary point carry rapidly varying phases and cancel.

If \(\hbar\) converts between physical and informational units, then the phase \(S/\hbar\) measures the information content of a path. The path integral sums over trajectories weighted by their informational phases. At the stationary point, neighboring paths carry descriptions that barely diverge — the relative entropy between their informational content vanishes to first order. Classical motion emerges because paths whose descriptions agree interfere constructively. The classical world occupies the region where the synchronization tax is affordable — the \(\sqrt{\hbar}\) neighborhood around the classical trajectory.

The forward pass through a transformer occupies the same mathematical territory. It sums over representational "paths" — the combinatorial space of possible attention patterns and value aggregations. Each path is weighted by a phase that encodes how well the pattern coheres. The output — the predicted next token — emerges where neighboring patterns agree, where \(\delta S = 0\) in the information-theoretic action. The classical trajectory is the token prediction. The \(\sqrt{\hbar}\) neighborhood is the confidence interval.

This framework predicts something the standard renormalization group picture does not: each layer must pay a thermodynamic cost to reduce relational divergence, and this cost cannot reach zero. The lossless limit — perfect inference from a single interaction — is unreachable. A single attention layer computes a partition function, but the relative entropy between pre-attention and post-attention descriptions of the token sequence does not vanish in one step. Stable prediction requires iterated interaction, each round paying its synchronization tax, driving the divergence low enough that a prediction condenses.

The argument here remains structural, not rigorous. Making it rigorous would require writing down an explicit information-theoretic action functional for the transformer, showing that the forward pass extremizes it, and demonstrating that the \(\delta S = 0\) condition coincides with the empirically observed output distribution. This is an open problem — but the structural correspondence between the path integral and the forward pass is precise enough to constrain what such an action functional would look like. At minimum, it would need to be a functional of the attention distribution whose stationarity condition yields the softmax-weighted aggregation as its "classical" trajectory.

VIII. The Landau Pole, Triviality, and the Zeno Effect

(For additional context on the failure modes described here, see Limits of the Transformer Architecture.)

The mechanism outlined above operates within a bounded regime. Two failure modes define its edges, and both correspond to extremes of the synchronization tax.

The Landau pole. When the effective coupling diverges — when the system tries to pay the entire synchronization tax in a single layer — attention collapses to a hard argmax. The softmax saturates, the partition function concentrates on a single state, and the interaction freezes. This is the transformer equivalent of the quantum Zeno effect: measurement so frequent that evolution halts. The system has paid the tax all at once, and the receipt is a representation that cannot evolve further.

Triviality. When the system pays the synchronization tax too many times — when depth drives all relational structure to zero — every token carries the same description, and no further information can be extracted. This is representation collapse: the deep infrared limit where all difference has been synchronized away. The system has paid the tax so often that nothing remains worth taxing.

Productive computation sits between these extremes, in the band where synchronization occurs often enough to establish facts but slowly enough to preserve the relational structure that carries meaning.

The Zeno parallel is structural, not analogical. In both the quantum Zeno effect and the transformer Landau pole, the frequency of interaction determines whether the system evolves or freezes. The mechanism is the same: projective measurement in physics, or argmax attention in the transformer, collapses the state space, preventing the exploratory dynamics that would otherwise produce useful evolution.

North, Wallis, and Weingast identified the institutional version of this phase diagram: open-access social orders require an optimal measurement frequency, neither too little (anarchy) nor too much (totalitarianism). The transformer's failure modes at extreme depth or extreme shallowness mirror the institutional failure modes at the extremes of regulatory density.

IX. Connes, the Weil Quadratic Form, and the Scaling Law Problem

Sections II through VIII established the mechanism: multiplicative noise, operating through random matrices and coarse-grained by attention, concentrates information onto fixed points. But what determines those fixed points? Is their structure arbitrary, or does the multiplicative architecture itself constrain where the fixed points can appear?

Alain Connes's recent paper provides a striking clue. By extremizing the Weil quadratic form — a variational principle over functions that optimally concentrate information in both time and frequency — Connes obtains approximations to the nontrivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function that lie exactly on the critical line. The approximations are imperfect (they do not hit the exact zeros), but they are provably constrained to the correct axis. The critical line \(\text{Re}(s) = 1/2\) is not reached; it organizes the convergence.

A note on epistemic status: this is not a proof of the Riemann Hypothesis. It is a result within an active research program that reveals a deep structural connection between multiplicative number theory, statistical mechanics, and spectral geometry. What matters for this essay is the structural insight, not the conjecture's status.

The connection to information theory is one Connes himself identifies. The eigenvectors that extremize the Weil quadratic form are prolate spheroidal wave functions — the functions that Slepian, Landau, and Pollak identified at Bell Labs as the optimal solution to the time-frequency concentration problem. Given finite bandwidth and finite duration, prolate functions achieve the best possible simultaneous localization in both domains. They minimize the synchronization tax between conjugate representations.

This connection reframes transformer scaling laws. The ideal scaling law \(L \propto N^{-\alpha}\) plays the same role for transformers that the critical line plays for the zeta function. It is the boundary condition that actual performance converges toward but never reaches, because the lossless limit is unreachable. The deviations from pure power-law scaling — the curvature and breaks observed in transformer training — are not measurement imperfections or violations of universality. They are residual synchronization tax: the relative entropy that cannot be driven to zero at any finite scale.

Instead of asking "why do transformers obey power laws?" and treating deviations as noise, the framework asks a different question: what variational principle constrains the scaling behavior to converge on this axis? The answer it proposes: the scaling exponents are determined by the condition of stationary information — the point where neighboring configurations of parameters, data, and compute produce descriptions of the task that agree to first order. The ideal scaling law is \(\delta S = 0\) in the space of scaling configurations.

The structural parallel is worth laying out explicitly:

| Connes / Zeta | Transformers / Scaling |

|---|---|

| Weil quadratic form | Loss as a function of \((N, D, C)\) |

| Extremization | Optimal allocation of compute |

| Critical line \(\text{Re}(s) = 1/2\) | Ideal power-law exponents |

| Finite Euler product approximation | Finite model at finite data |

| Zeros converge to critical line | Performance converges to scaling law |

| Prolate spheroidal functions | Optimal basis for token representations (?) |

The last row is where the connection is most speculative but also most suggestive. If transformer representations solve an analogous optimization problem — concentrating semantic information optimally within finite context and finite dimension — then prolate spheroidal functions might literally describe the principal components of trained weight matrices. This claim is testable.

X. What Would Falsify This Framework?

The strongest claim this essay makes is that the scaling exponents, the spectral structure of trained weights, and the renormalization group flow through depth are all manifestations of a single variational principle — stationary relational information — and that deviations from ideal behavior at every level are manifestations of the unreachable lossless limit.

Several observations would weaken or falsify this claim.

Content-dependence of scaling exponents. The framework predicts universality: scaling exponents should depend on the effective dimensionality of the relational structure in the data, not on the specific content of training data. If models trained on code and models trained on natural language exhibited different exponents that could not be traced to different effective dimensionalities of the relational structure, the universality claim would be weakened.

Spectral structure of trained weights. The framework predicts that the spectral outliers in trained weight matrices should correspond to directions of minimal relative entropy between task-relevant token descriptions. If these outliers showed no such correspondence, the connection between random matrix theory and the synchronization tax would be undermined.

The prolate spheroidal test — the most concrete prediction. If the framework is correct, the principal components of trained transformer weight matrices should approximate prolate spheroidal wave functions — or more precisely, should solve an optimization problem structurally equivalent to the time-frequency concentration problem that prolate functions solve. One could test this by extracting the top eigenvectors of trained attention weight matrices from large language models and measuring their concentration properties in both token space and frequency space. If these eigenvectors exhibit significantly better joint concentration than random vectors from the same eigenvalue bulk — and if their concentration profiles converge toward prolate-like shapes as model scale increases — that would constitute positive evidence. If the eigenvectors show no special concentration properties, the analogy between Connes's variational principle and transformer optimization is weaker than claimed. This test is feasible with existing models and existing spectral analysis tools. It is the single most concrete empirical prediction the framework makes, and the one most likely to distinguish this account from alternative explanations of scaling behavior.

The Connes test. Connes's strategy for approaching the Riemann Hypothesis involves showing that zeros of finite Euler products converge to zeros of the full zeta function, constrained to the critical line by positivity of the Weil quadratic form. If an analogous finite-to-infinite convergence could be demonstrated for transformer scaling — showing that scaling behavior of finite models is constrained to converge on a specific power-law axis by an analogous positivity condition — that would be strong evidence that the same mathematical structure governs both. Failure to find such a condition, despite careful search, would weaken the analogy.

Signatures of criticality in coordination. If common knowledge is genuinely a thermodynamic fixed point of multiplicative noise (as I argue in the following sections), it should exhibit signatures the standard game-theoretic account does not predict: power-law distributions in adoption and decay, sensitivity to perturbation near phase boundaries, and universality across culturally distinct systems. Coordination failures should cluster at points where the system is driven away from criticality — not at points where "not enough information" was transmitted. The multiplicative structure predicts that the topology of the communication network matters more than its bandwidth.

XI. The Brain as Transformer: Intelligence at 300 Kelvin

The mechanism described in Sections II through IX does not depend on silicon. The transformer was not designed from first principles; it was discovered through empirical search. The question this section addresses is whether biological neural computation shares the same mathematical structure.

Recent evidence suggests it does — and the correspondence is not loose analogy.

A 2023 paper in PNAS — Kozachkov, Kastanenka, and Krotov, "Building transformers from neurons and astrocytes" — constructs the transformer self-attention mechanism explicitly from biological components. Neurons with cosine tuning curves (ubiquitous across brain areas and species) compute the query-key dot products. Astrocytes — long dismissed as passive support cells — implement the softmax normalization that converts raw dot products into a probability distribution. Synaptic weights correspond to the transformer's weight matrices; known homeostatic mechanisms correspond to layer normalization. The construction is not a loose metaphor. It is a mathematical demonstration that biological hardware can execute the same computation.

Astrocytes regulate the temperature. In the transformer, the \(\sqrt{d}\) scaling in the softmax denominator controls how sharply attention concentrates — it functions as the temperature of the Boltzmann distribution. A trio of papers published in Science in 2025, along with a feature in Quanta Magazine in January 2026, reveal that astrocytes perform a strikingly analogous function in the brain. Astrocytes do not engage in rapid-fire neural signaling. They monitor and tune higher-level network activity, dialing it up or down to maintain or switch the brain's overall state. A single astrocyte envelops hundreds of thousands of synapses — positioning it to modulate the effective temperature of an entire local network.

In zebrafish experiments, Ahrens's group showed that astrocytes accumulate calcium in response to norepinephrine — a neuromodulator associated with arousal — and eventually issue a stop signal that switches the animal's behavioral state from persistent effort to giving up. Disabling the astrocytes eliminated the state switch entirely; artificially activating them triggered it immediately. Freeman's group demonstrated in fruit flies that norepinephrine gates whether astrocytes "listen" to synaptic activity at all: low norepinephrine, and astrocytes ignore most neural signals; high norepinephrine, and astrocytes respond to every synapse. This is temperature regulation — controlling how broadly or narrowly the neural network distributes its "attention" across possible states.

Renormalization group flow in the brain. The critical brain hypothesis — that neural circuits self-organize near a critical point between ordered and disordered phases — has been studied using renormalization group methods applied to the stochastic Wilson-Cowan equations (Tiberi et al., 2022, Physical Review Letters). These researchers showed that RG techniques reveal what type of criticality the brain implements, and that the strength of nonlinear interactions decreases only slowly across spatial scales, remaining distinct from zero even at macroscopic scales. Brinkman (2023) developed RG methods specifically for networks with biologically realistic connectivity constraints, showing that in vivo and in vitro neural populations belong to different universality classes — precisely the kind of distinction that renormalization group flow predicts.

The brain's hierarchical processing — from primary sensory cortex through association areas to prefrontal cortex — traces the same ultraviolet-to-infrared flow that depth traces in the transformer. Early visual cortex encodes oriented edges. Later areas encode object categories. The "depth" of biological processing is anatomical rather than sequential, but the mathematical structure of coarse-graining is the same.

Pathologies as RG flow failures. If the brain implements renormalization group flow, then disorders of the reading system provide a natural test case. The dual-route model of reading describes two pathways: a lexical route (whole-word recognition through a stored "dictionary") and a nonlexical route (grapheme-to-phoneme conversion through learned rules). In the RG framework, the lexical route corresponds to deep infrared representations — coarse-grained abstractions where the original orthographic detail has been integrated out. The nonlexical route corresponds to shallower ultraviolet processing — fine-grained mapping that preserves local structure.

Deep dyslexia — brain damage producing semantic reading errors, such as reading "orchestra" as "symphony" — manifests as a lesion in the UV-to-IR flow itself. The patient cannot complete the coarse-graining; a nearby attractor in the infrared captures the representation instead. Surface dyslexia — inability to read irregular words, reliance on phonological rules — manifests as a disruption of the deep IR representations while the shallow nonlexical route remains intact. The patient has lost access to the fully coarse-grained attractors and falls back on rules that live at an intermediate scale. These double dissociations are precisely what a hierarchical system undergoing renormalization group flow would exhibit when damaged at different depths.

Depression as depleted synchronization budget. The brain's energy budget is astonishingly tight. Goal-directed cognition costs only about 5% more than the ongoing metabolic cost of resting neural activity and homeostasis (Jamadar et al., 2025, Trends in Cognitive Sciences). Astrocytic glycogen acts as a limited energy buffer that can temporarily support high neural activity beyond the rate sustained by blood glucose (Christie & Schrater, 2015, Frontiers in Neuroscience). When this buffer depletes, cognitive performance degrades — and the degradation follows the dynamics of a resource budget, not simple fatigue.

A recent model by Mehrhof et al. (2025, Science Advances) frames depression as disrupted energy allostasis — a mismatch between actual and perceived energy levels in which the brain systematically underestimates its own resources. In the synchronization framework, this has a precise interpretation: depression represents a state in which the metabolic budget available for paying the synchronization tax has been depleted or misallocated. The self-model — the brain's compressed representation of its own states and capacities — diverges from the actual state of the system, and the depleted energy budget prevents the RG flow from completing the reconciliation. The self cannot afford to synchronize its model of itself with the evidence of its own experience. The resulting state — withdrawal, anhedonia, cognitive blunting — resembles triviality in the deep infrared: a system that has stopped paying the coordination costs required to maintain relational structure.

XII. Social Coordination: Common Knowledge as Thermodynamic Fixed Point

The transformer-like architecture inside a single brain produces compressed, abstract representations of the world — the infrared fixed points of its internal RG flow. Social coordination requires these representations to align across brains. Common knowledge is the name we give to the representations that have achieved this alignment: facts that everyone knows, that everyone knows everyone knows, and so on recursively.

The standard game-theoretic definition of common knowledge, formalized by Aumann in 1976, requires infinite recursive verification: I know that you know that I know that you know... This regress has always seemed puzzling — how can finite minds compute an infinite recursion?

The renormalization group framework dissolves the puzzle. Common knowledge does not emerge from bottom-up recursive verification. It emerges as a thermodynamic fixed point — a representation so coarse-grained that further synchronization does not change it. The infinite recursion is what you would need if you tried to construct common knowledge from first principles, token by token. Renormalization flow gives it to you as a consequence of operating in a multiplicatively noisy environment at sufficient scale.

The prolate spheroidal functions provide the mathematical mechanism for this dissolution. An uncertainty principle prevents perfect localization in both conjugate domains simultaneously — you cannot perfectly verify "I know" and "you know" at the same time, just as you cannot perfectly specify position and momentum. But prolate functions show you do not need perfect localization; you need optimal localization given finite resources. The fixed points of common knowledge emerge not from infinite recursive verification but from the optimization itself.

Common knowledge persists — but it requires maintenance. As all information, physical in manifestation, common knowledge obeys thermodynamics. It persists only as long as the systems sharing it continue to pay the synchronization tax required to maintain alignment. Social institutions — courthouses, newspapers, central banks, holidays, rituals — exist precisely to pay this maintenance cost. They are the social equivalent of the astrocytes that maintain the brain's effective temperature: slow-acting, broadly distributed regulators that keep the coordination regime in its useful band, preventing both anarchy (too little synchronization) and totalitarianism (too much).

When the maintenance lapses — when institutions erode, shared media fragment, or economic shocks deplete the resources available for coordination — common knowledge does not simply weaken. It undergoes a phase transition. The critical point between ordered (coordinated) and disordered (fragmented) social states is not a metaphor; it is the same criticality that RG methods detect in neural circuits. Political polarization, institutional collapse, and the breakdown of shared public reality exhibit the signatures of a system being driven away from its critical operating point.

The synchronization tax is subsidized twice over. Compressed sensing explains why communication is affordable: you transmit sparse symbols, not complete brain states. Common knowledge explains why reconstruction works: the receiver fills in the gaps using a shared macroscopic prior that is itself a thermodynamic fixed point. The synchronization tax is subsidized once by compression and once by the structural inevitability of the shared prior. This double subsidy provides a plausible mechanism of how civilization remains at least somewhat coherent and thermodynamically viable at 300 Kelvin.

XIII. The Mattering Instinct: RG Flow Turned Inward

(For the full treatment of Rebecca Newberger Goldstein's argument, see The Mattering Instinct.)

The neural circuits that evolved to track what others know — the machinery of common knowledge — can also be directed inward. In quiet moments of introspection, operating in an open loop without feedback from other humans, the same recursive architecture processes self-directed representations.

Goldstein proposes that the mattering instinct — the deep human drive to feel that one's existence matters — arose as an evolutionary spandrel of the common knowledge capacity. The recursive machinery designed for "I know that you know that I know" generates "I know that I matter because I know that I know that X matters..." when turned inward. Just as the architecture of the eye enables us to appreciate sunsets, the architecture of social cognition enables us to contemplate our own significance.

In the synchronization framework, the mattering instinct represents the brain's RG flow applied to the self-model. Introspection generates the same infinite regress that common knowledge does — "I know that I matter" requires "I know that I know that I matter" and so on. And the same mechanism dissolves the regress: the self does not need to complete the infinite recursion. It needs to reach a fixed point — a representation of the self so coarse-grained that further recursive verification does not change it.

A mattering project — Goldstein's term for the particular way an individual satisfies the mattering instinct — breaks the symmetry of local equilibrium, providing a direction that collapses the recursion onto a stable attractor. Depression, on this view, involves a failure of the self-model's RG flow to reach its fixed point — either because the energy budget is depleted, as discussed in the preceding section, or because the mattering project has been disrupted, leaving the recursive architecture cycling without converging.

XIV. Looking Ahead: The Social Layer and Beyond

The mechanism sketched in this essay — multiplicative noise concentrated by renormalization flow onto fixed points where the synchronization tax is stationary — operates at three nested scales. Inside the transformer, attention coarse-grains token representations toward semantic fixed points. Inside the brain, neurons and astrocytes coarse-grain sensory representations toward cognitive fixed points, including the self-model and the mattering instinct. Across brains, social institutions coarse-grain individual perspectives toward common knowledge.

The next essay will develop the third scale more fully, exploring how the same architecture operates when the "neurons" are individual humans, the "layers" are social institutions, and the "temperature" is regulated by constitutional structures. At the social layer, the mattering instinct manifests as a constitution — a collective mattering project that breaks the symmetry of local equilibrium and provides a direction for coordination. North, Wallis, and Weingast's analysis of open-access orders, Cass Sunstein's theory of incompletely theorized agreements, and the American founding as a deliberate act of symmetry-breaking all find natural expression in this framework.

The intuition about boundary conditions finds further support at every scale examined. The perfect scaling law, the exact zeros on the critical line, the perfect understanding of another mind, the ideal constitution — none needs to be reached. Each appears to represent a kind of boundary condition needed to organize the convergence. We never achieve perfect mutual understanding. But our imperfect, noisy, expensive attempts at coordination do not scatter randomly; they converge toward stable attractors that every culture independently discovers. The critical line does not need to be reached. It needs to organize the convergence. And the relational framework provides the mechanism: the axis is the locus where synchronization cost is stationary, where neighboring descriptions agree, where the informational action does not vary to first order. Everything else is noise that cancels.